Optical telescopes – telescopes that collect visible light – show us shining stars, glowing gas and dark dust but this doesn't give us the whole picture of what's happening in space. Telescopes tuned to different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum can reveal hidden objects in space; the resulting images can then be combined to give a more complete picture.

Radio waves from space were first detected in the 1930s but little was done to follow them up until after the Second World War. In the post-war period CSIRO scientists and engineers were among the pioneers of radio astronomy.

Radio telescopes 'tune in' to the Universe

In much the same way that you tune the radio to a particular station, radio astronomers can tune their telescopes to pick up radio waves millions of light years from Earth. Using sophisticated computer programming, they can unravel signals to study the birth and death of stars, the formation of galaxies and the various kinds of matter in the Universe.

In its simplest form a radio telescope has three basic components:

- One or more antennas pointed to the sky, to collect the radio waves

- A receiver and amplifier to boost the very weak radio signal to a measurable level, and

- A recorder to keep a record of the signal.

Radio telescopes can be used both night and day, and CSIRO's telescopes are operated around the clock.

Radio astronomers 'see' the invisible Universe

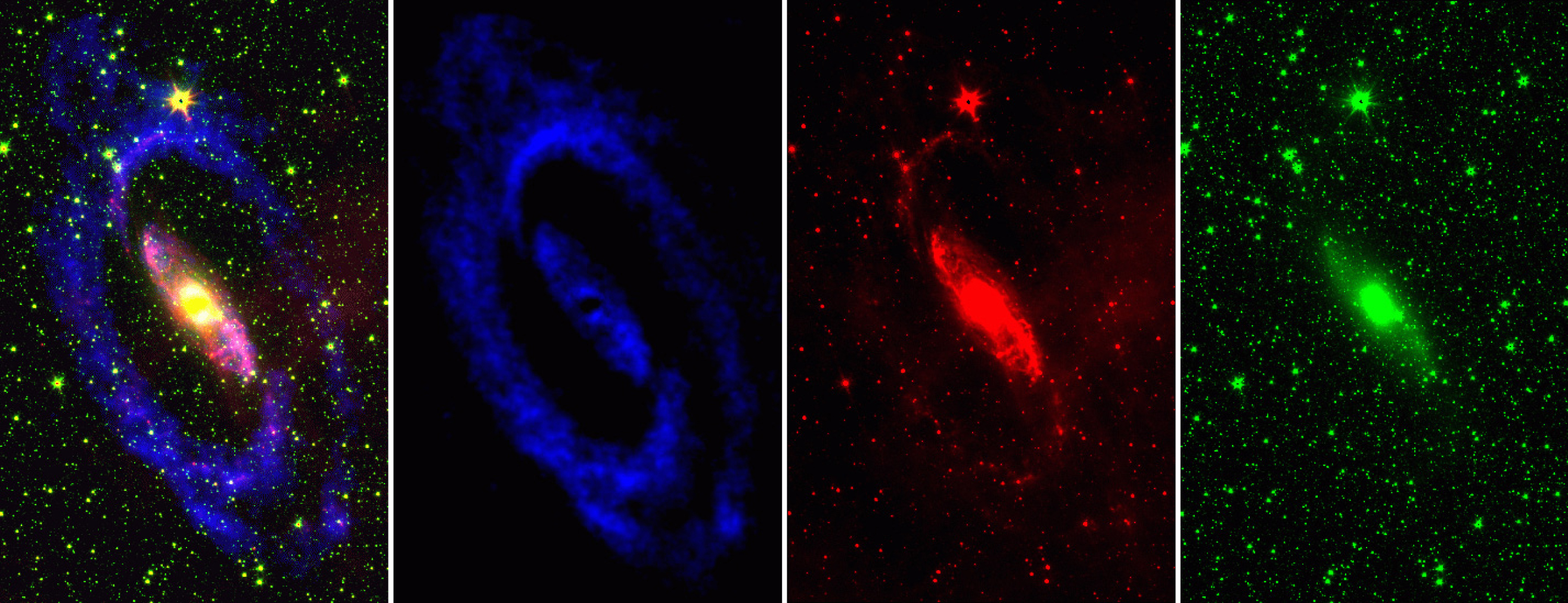

Radio astronomers process the masses of information collected by a telescope. To help make sense of the strings of numbers, they convert the numbers into pictures. Each number represents information from a specific point in space. Often they have colours assigned to the numbers corresponding to the amount of information they represent. Astronomers then combine the colours to make a picture, visualising the information to reveal some of the characteristics of objects in the Universe.

What do we learn from radio astronomy?

Radio astronomy has changed the way we view the Universe and dramatically increased our knowledge of it, for example:

- Astronomers trying to identify the source of interference in a radio antenna in the 1960s discovered the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation, the afterglow of the Big Bang.

- Cold clouds of gas found in interstellar space emit radio waves at distinct wavelengths. As hydrogen is the most abundant element in the Universe and is common in galaxies, radio astronomers use its characteristic emission to map out the structure of galaxies.

- Radio astronomy has also detected many new types of objects including pulsars, the rapidly spinning remnants of supernova explosions that send out regular flashes of radio waves much like the beam from a lighthouse. Murriyang, our Parkes radio telescope, has detected over half of the more than 2000 known pulsars.

How can radio astronomy be applied elsewhere?

The science and engineering behind radio astronomy can also benefit our everyday lives, for instance:

- Our fast wireless LAN technology, which was developed from our expertise in radio astronomy and led to 'fast Wi-Fi', is now the way most of us access the internet without wires.

- Pulsars offer potential as extremely accurate clocks and are possible alternatives to satellite-based global positioning systems.

- For our newest radio telescope, ASKAP, we developed innovative 'phased array feed' receivers with a wide field-of-view. This is the first time that this type of technology has been used in radio astronomy and offers enormous potential for other applications such as satellite communications.

Optical telescopes – telescopes that collect visible light – show us shining stars, glowing gas and dark dust but this doesn't give us the whole picture of what's happening in space. Telescopes tuned to different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum can reveal hidden objects in space; the resulting images can then be combined to give a more complete picture.

Radio waves from space were first detected in the 1930s but little was done to follow them up until after the Second World War. In the post-war period CSIRO scientists and engineers were among the pioneers of radio astronomy.

Radio telescopes 'tune in' to the Universe

In much the same way that you tune the radio to a particular station, radio astronomers can tune their telescopes to pick up radio waves millions of light years from Earth. Using sophisticated computer programming, they can unravel signals to study the birth and death of stars, the formation of galaxies and the various kinds of matter in the Universe.

In its simplest form a radio telescope has three basic components:

- One or more antennas pointed to the sky, to collect the radio waves

- A receiver and amplifier to boost the very weak radio signal to a measurable level, and

- A recorder to keep a record of the signal.

Radio telescopes can be used both night and day, and CSIRO's telescopes are operated around the clock.

Radio astronomers 'see' the invisible Universe

Radio astronomers process the masses of information collected by a telescope. To help make sense of the strings of numbers, they convert the numbers into pictures. Each number represents information from a specific point in space. Often they have colours assigned to the numbers corresponding to the amount of information they represent. Astronomers then combine the colours to make a picture, visualising the information to reveal some of the characteristics of objects in the Universe.

What do we learn from radio astronomy?

Radio astronomy has changed the way we view the Universe and dramatically increased our knowledge of it, for example:

- Astronomers trying to identify the source of interference in a radio antenna in the 1960s discovered the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation, the afterglow of the Big Bang.

- Cold clouds of gas found in interstellar space emit radio waves at distinct wavelengths. As hydrogen is the most abundant element in the Universe and is common in galaxies, radio astronomers use its characteristic emission to map out the structure of galaxies.

- Radio astronomy has also detected many new types of objects including pulsars, the rapidly spinning remnants of supernova explosions that send out regular flashes of radio waves much like the beam from a lighthouse. Murriyang, our Parkes radio telescope, has detected over half of the more than 2000 known pulsars.

How can radio astronomy be applied elsewhere?

The science and engineering behind radio astronomy can also benefit our everyday lives, for instance:

- Our fast wireless LAN technology, which was developed from our expertise in radio astronomy and led to 'fast Wi-Fi', is now the way most of us access the internet without wires.

- Pulsars offer potential as extremely accurate clocks and are possible alternatives to satellite-based global positioning systems.

- For our newest radio telescope, ASKAP, we developed innovative 'phased array feed' receivers with a wide field-of-view. This is the first time that this type of technology has been used in radio astronomy and offers enormous potential for other applications such as satellite communications.