A new public risk from a virus

In May 1996 a black flying fox showing nervous signs was found near Ballina, NSW.

In May 1996 a black flying fox showing nervous signs was found near Ballina, NSW.

Samples from the flying fox were sent to Yeerongpilly Veterinary Laboratory in Queensland as part of a surveillance program for the Hendra virus and a fixed-tissue brain sample was sent to CSIRO's Australian Animal Health Laboratory (AAHL) in Geelong, Victoria.

The Hendra virus tests were negative, but virus isolation and gene sequencing showed that it was a lyssavirus, which is closely related to the rabies virus.

Later that year a Queensland woman who had recently become a bat handler, became ill. The initial numbness and weakness suffered in her arm progressed to coma and death. Samples sent to AAHL confirmed that she had been infected with lyssavirus.

Two further cases in Queensland - a woman in 1998 and an eight year old boy in 2013 - resulted in death after being bitten or scratched by a bat.

Lyssavirus has been isolated, or infection demonstrated, in fruit bats (flying foxes) from:

- New South Wales

- Northern Territory

- Queensland

- Victoria

- Western Australia

As well as in insectivorous bats in Queensland and NSW. Australia's rabies-free status has not changed as a result of the Australian bat lyssavirus discovery.

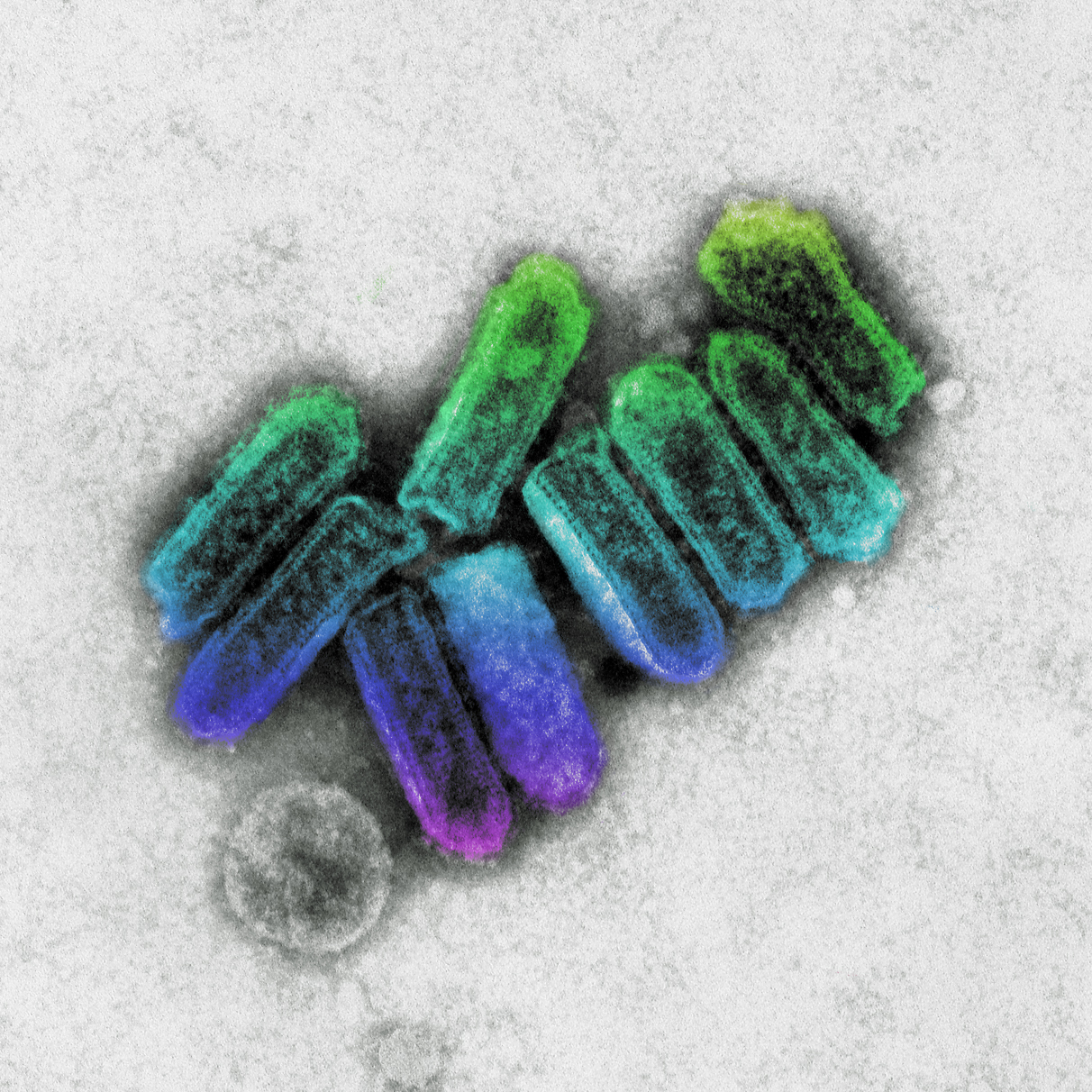

Understanding lyssavirus

Research has provided information about the gene and protein structure of the virus. This has allowed scientists to refine the tests available.

AAHL research shows there are subtle differences between lyssavirus in flying foxes and insectivorous bats. This indicates there are two established cycles of the virus in Australia:

- one in flying foxes

- another in insectivorous bats.

Infected bats are capable of transmitting the virus to:

- people

- other bats

- other mammals.

Research shows that some, but not all, infected bats had virus in their saliva or salivary glands. Retrospective studies have identified no further human cases of Australian bat lyssavirus.

Investigation of stored bat tissue has so far identified virus in specimens collected as early as January 1995.

Protection from and prevention of bat-borne diseases

People

Australian health authorities suggest lyssavirus poses a low public health risk however, they strongly recommend that anyone scratched or bitten by a bat should immediately wash the affected area with soap and water and contact their local doctor.

Research shows the vaccine for classical rabies has a high degree of cross-protection against lyssavirus.

A pre-exposure course of rabies vaccine should be taken by high-risk category people, such as:

- bat carers

- veterinarians

- wildlife officers.

There is also a post-exposure treatment course for people bitten or scratched by a bat which may be infected.

Pets

If your pet has contact with a bat, animal health authorities advise you to contact your state agriculture department or veterinarian for advice.

The Department of Health advises that the risk of transmission of bat lyssavirus from a dog or cat to a person is very low, although there is theoretical risk of transmission.

A new public risk from a virus

In May 1996 a black flying fox showing nervous signs was found near Ballina, NSW.

Samples from the flying fox were sent to Yeerongpilly Veterinary Laboratory in Queensland as part of a surveillance program for the Hendra virus and a fixed-tissue brain sample was sent to CSIRO's Australian Animal Health Laboratory (AAHL) in Geelong, Victoria.

The Hendra virus tests were negative, but virus isolation and gene sequencing showed that it was a lyssavirus, which is closely related to the rabies virus.

Later that year a Queensland woman who had recently become a bat handler, became ill. The initial numbness and weakness suffered in her arm progressed to coma and death. Samples sent to AAHL confirmed that she had been infected with lyssavirus.

Two further cases in Queensland - a woman in 1998 and an eight year old boy in 2013 - resulted in death after being bitten or scratched by a bat.

Lyssavirus has been isolated, or infection demonstrated, in fruit bats (flying foxes) from:

- New South Wales

- Northern Territory

- Queensland

- Victoria

- Western Australia

As well as in insectivorous bats in Queensland and NSW. Australia's rabies-free status has not changed as a result of the Australian bat lyssavirus discovery.

Understanding lyssavirus

Research has provided information about the gene and protein structure of the virus. This has allowed scientists to refine the tests available.

AAHL research shows there are subtle differences between lyssavirus in flying foxes and insectivorous bats. This indicates there are two established cycles of the virus in Australia:

- one in flying foxes

- another in insectivorous bats.

Infected bats are capable of transmitting the virus to:

- people

- other bats

- other mammals.

Research shows that some, but not all, infected bats had virus in their saliva or salivary glands. Retrospective studies have identified no further human cases of Australian bat lyssavirus.

Investigation of stored bat tissue has so far identified virus in specimens collected as early as January 1995.

Protection from and prevention of bat-borne diseases

People

Australian health authorities suggest lyssavirus poses a low public health risk however, they strongly recommend that anyone scratched or bitten by a bat should immediately wash the affected area with soap and water and contact their local doctor.

Research shows the vaccine for classical rabies has a high degree of cross-protection against lyssavirus.

A pre-exposure course of rabies vaccine should be taken by high-risk category people, such as:

- bat carers

- veterinarians

- wildlife officers.

There is also a post-exposure treatment course for people bitten or scratched by a bat which may be infected.

Pets

If your pet has contact with a bat, animal health authorities advise you to contact your state agriculture department or veterinarian for advice.

The Department of Health advises that the risk of transmission of bat lyssavirus from a dog or cat to a person is very low, although there is theoretical risk of transmission.