On a warm morning on Wajarri Country in outback Western Australia (WA), Emily Goddard and Wajarri man Lockie Ronan are starting their day at 5.30am.

They are several weeks into their roles with us and the SKA Observatory (SKAO) as field technicians for the SKAO’s low-frequency telescope, SKA-Low.

But it’s no ordinary workday. This remote site, almost five hours’ drive from the coastal city of Geraldton, with red earth spanning as far as the eye can see, is a hive of activity.

Lockie and Emily are helping the SKAO install the first of 131,072 antennas that will make up the SKA-Low telescope at Inyarrimanha Ilgari Bundara, our Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory.

Emily and Lockie are two of 10 field technicians who are building and installing the first SKA-Low antennas, together with a team of SKA-Low staff from Australia and the SKAO’s headquarters in the UK.

Those joining them have been working towards the SKA project for anywhere from one month to 30 years. It is an ambitious international collaboration to revolutionise our understanding of the Universe. The SKA project is led by the SKAO, which is currently building the SKA-Low and SKA-Mid telescopes.

“We’ve prepared the area for our first antenna assembly,” Emily says.

"We’ve put our big workshop tent up, we’ve got antennas ready, got tools ready, got the team ready. We’re excited. It’s all happening.”

This is an important milestone for the first mega-science project on Australian soil.

Partnering with the Wajarri Yamaji People

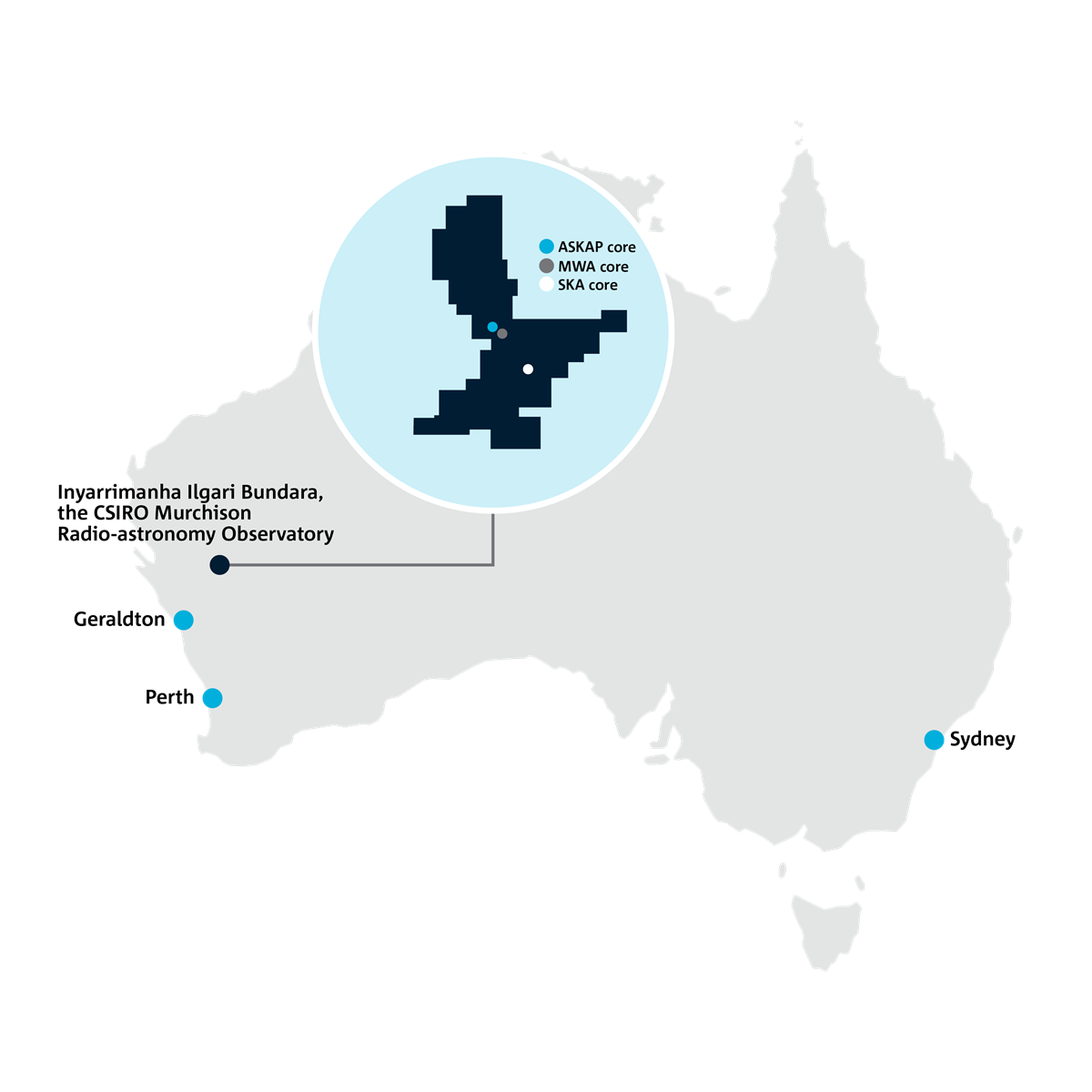

The Australian bid to host the SKA telescopes began more than 20 years ago. The search led to the remote Murchison region of WA: the ancient, sparsely populated, open lands of Wajarri Country.

This region is internationally recognised as one of the best places in the world to do radio astronomy. The remote location – far from radio interference with a magnificent view of the southern sky, peering into the centre of our galaxy – is exceptional.

This land is the home of the Wajarri Yamaji People, the Traditional Owners and native title holders of the observatory site. They are essential partners in building the SKA-Low telescope.

We have worked with the Wajarri Yamaji for almost two decades. Our partnership established the observatory on Country with the support of the Australian and WA governments.

Our Director of Space and Astronomy, Dr Douglas Bock, is familiar with the unique beauty of Wajarri Country. He first set foot in the Murchison in 2010, when he was working on our ASKAP radio telescope at the observatory site.

He says the contribution the Wajarri Yamaji are making to the SKA project cannot be overstated.

“The deep Wajarri connection to Country is working in harmony with humanity’s desire to explore and understand the Universe around us,” Douglas says.

“The Wajarri Yamaji People are playing a key part in extending our shared knowledge of the Universe. Over many years they have generously shared their knowledge of Country with our team as we built the existing telescopes on site and prepared to host the SKA-Low telescope,” he says.

The world’s largest radio telescopes

Built by the SKAO, an international collaboration involving 16 countries including Australia, the SKA telescopes will be the world’s largest and most sensitive radio telescopes.

We're collaborating with the SKAO to build and operate the SKA-Low telescope in Australia. This is an array of 131,072 two-metre-tall, Christmas tree-shaped, silver metal antennas to be installed on the rich, red soil of the Murchison.

Its ‘sister' telescope, SKA-Mid, will be 197 15m-wide dish-shaped antennas spread over the Karoo in South Africa.

Protecting Country during SKA-Low construction

Since the SKAO celebrated the start of on-site construction in December 2022, the focus has been laying the groundwork for antenna installation.

Led by infrastructure contractor Ventia, the ground has been prepared. Expansive silver circles of steel mesh for the antennas to sit on have begun to be placed. Trenches are being dug to lay the cables that will power and transport the vast amounts of data captured by the telescope.

It's paramount to us, the SKAO, and the Wajarri that cultural heritage is protected during construction. Wajarri Yamaji heritage monitors are a vital fixture on site, working alongside the construction teams for all ground disturbing activities.

We both worked together with Wajarri teams to finalise a layout for the telescope. Its central core and three spiral arms dotted with antenna stations spread across 74km end-to-end. This design coexists with significant Wajarri sites and ensures Wajarri culture is protected for future generations.

An Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA), negotiated over many years by the Wajarri Yamaji with us, the Australian and WA governments, underpins the cultural heritage protection on site. It also provides the Wajarri Yamaji with sustainable and intergenerational benefits in areas including education, enterprise and training.

Jennylyn Hamlett, a proud Wajarri woman and Wajarri Aboriginal Liaison Officer, was part of the negotiation team for the ILUA. She is making sure the ILUA benefits are reaching her community.

“It’s our security blanket, it protects what we have out there, because without our culture we have nothing,” Jennylyn Hamlett says.

“We rely on our culture, it’s a priority to our Wajarri People."

“When we came to the conclusion that the Wajarri Yamaji would be a partner and walk side-by-side with SKAO and CSIRO, it was for the betterment of our future generations – to empower our children.”

The Wajarri Yamaji have been observing the sky and stars on Country for tens of thousands of years. Now they are sharing the same skies with radio telescopes seeking to discover the secrets of the Universe.

With the signing of this historic ILUA, the Wajarri gifted a traditional name to the observatory: Inyarrimanha Ilgari Bundara – which means ‘sharing the sky and stars’ in the Wajarri language.

What will the SKA-Low telescope be looking for?

As a teenager, astronomer Dr Sarah Pearce set her sights on a career studying the stars.

Sarah is one of the many astronomers who’ve spent decades looking forward to construction of the SKA telescopes. Now she is the SKA-Low Telescope Director based in Perth.

Sarah says the SKA-Low telescope will investigate that shared sky and stars in incredible detail.

Dr Sarah Pearce meets with members of the SKA-Low construction team on site at Inyarrimanha Ilgari Bundara, our Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory on Wajarri Yamaji Country. Credit: SKAO.

“The SKA-Low telescope will be like a time machine,” Sarah says.

“This powerful telescope will look back to when the Universe was in its infancy, when the first stars and galaxies were born. We’ll look back and see things never seen before.”

She says the telescope may look unusual, but its unique design will allow it to map the sky faster than any telescope before it.

“SKA-Low will be so sensitive that it can collect the faintest radio signals that have travelled billions of light years across the Universe. It will allow us to test Einstein's theories and to observe space in more detail than ever, but I’m most excited about the things we’ll discover that we’ve never even thought of,” Sarah says.

How do you build a world-leading radio telescope?

Lockie and Emily are on the ground working to bring this 30-year plan to fruition.

Lockie says it’s fantastic to be working on such a revolutionary project.

“It means a lot to me spiritually that I get to be out on Country, connecting with the land and my culture while I work,” Lockie says.

“My parents and grandparents are proud and ecstatic to know I’m out here working on this project on my Pop’s land.”

They are some of the first field technicians to join us in roles that were created together with the SKAO and co-designed with Wajarri Yamaji representatives and Geraldton’s Central Regional TAFE.

Leonie Boddington is a language worker, who assisted in producing the Wajarri dictionary. She is passionate about her language and culture and lends her knowledge to us as our Aboriginal Liaison Officer.

Leonie is involved in supporting the field technician roles, alongside involvement from Jennylyn Hamlett and other Wajarri representatives.

“Being able to develop an opportunity like this for our Wajarri community is fantastic,” Leonie says.

“We’ve been preparing for the SKA-Low telescope for years and to have Wajarri field technicians out there on Country is what it’s all about.”

Leonie helps build an SKA-Low antenna with support from a SKA-Low field technician. Credit: SKAO.

The partnership is already seeing success – 70 per cent of the first field technician cohort are Wajarri Yamaji.

“Our involvement to develop the new roles has made sure the support is there for Aboriginal participants,” Leonie says.

Members of the SKA-Low team act as mentors for the field technicians. The Indigenous members of the team are also supported by Leonie as cultural mentor.

The SKA-Low field technicians are learning about the entire telescope system from the ground up. They’ll soon be the on-the-ground world-experts in the SKA-Low telescope’s components.

Emily says she’s already learned a lot since she joined the SKA-Low team.

“I don’t come from a background of engineering or building or technology or science. I’m very lucky to work in a place where everyone is happy to share their knowledge, everyone wants to tell you about their field of expertise. I’ve learned about every aspect of the telescope and where it’s going.”

Emily Goddard, SKA-Low Field Technician

What makes up the world’s largest radio telescopes?

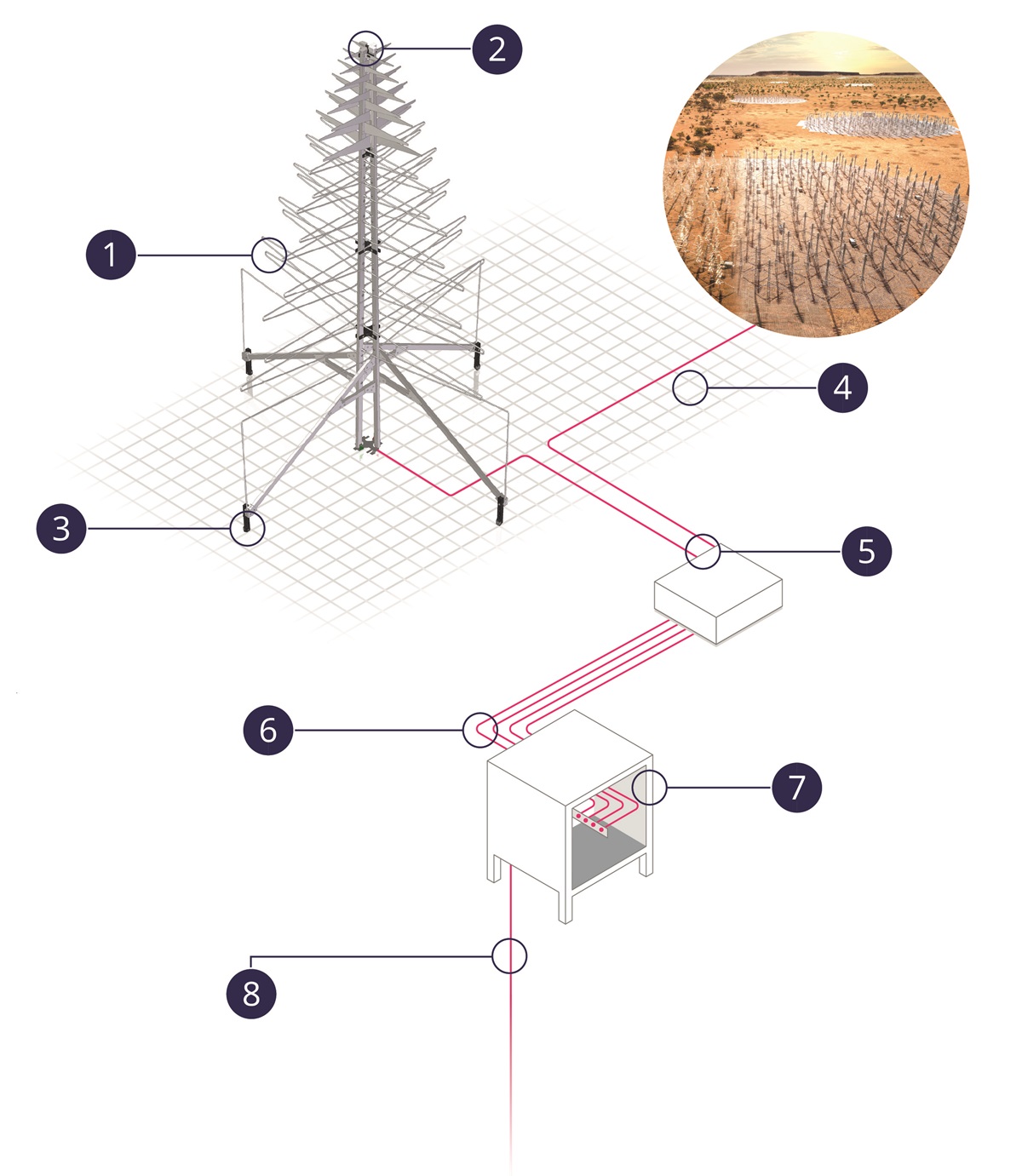

What makes up the SKA-Low, one of the world’s largest radio telescopes?

Every component of the SKA-Low telescope has been carefully designed to achieve its ambitious science goals while withstanding the remote and exposed environment of the observatory site.

The SKA-Low telescope will ultimately have 512 stations, each a circular group made up of 256 individual antennas.

1. Antenna ‘dipoles’: Radio frequency light waves from the Universe excite the antenna dipoles, generating an electrical current. The SKA-Low antennas observe the same frequencies used by AM/FM radio and digital TV.

2. Low noise amplifiers: The electrical signals transmit via cabling inside the antennas to LNAs (low noise amplifiers) that amplify the weak signals collected from space.

3. Clip feet: Clips hold the antennas onto the mesh, keeping them upright and in position in the wide variety of weather conditions encountered at the observatory.

4. Mesh: Steel mesh creates a consistent base for the antennas, ensuring they can best collect the signals from the Universe.

5. Smart boxes: Smart boxes (24 per station) convert electrical currents received and amplified by the antennas into signals that can be passed through optical fibre. They also power the LNAs.

6. Optical fibre and power: Data flows at 100 Gb/s down the optical fibre from each set of six stations, adding together to 7.2Tb/s flowing from site for the entire telescope. The on-site optical fibre and power cabling from the SKA-Low stations will be almost 1,000km long!

7. Field node distribution hubs (FNDHs): These boxes (one per station) distribute power to the smart boxes and monitor the antennas and telescope components.

8. Data flows to on-site processing facilities… and beyond

From each station’s field node distribution hub, data flows to the on-site supercomputer at the central processing facility near the telescope’s core. Distant stations along the spiral arms connect to remote facilities that in turn pass data on to this central supercomputer.

At the on-site computing signals from each antenna station are digitised, time stamped, and interference is removed. The signals then undertake the long trip to the Pawsey Supercomputing Research Centre, 700km away in Perth.

At Pawsey, another supercomputer will combine the signals from multiple stations so they act as one giant telescope, producing images of the sky.

These images will be distributed to the science community by a network of regional supercomputing centres across SKAO member countries. From these regional centres astronomers will access their SKA data to investigate, and maybe discover something new.

A day in the life of building the SKA-Low telescope

For field technicians such as Lockie and Emily, most of their work time is spent on Country at Inyarrimanha Ilgari Bundara, our Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory.

Their home for the week is Nyingari Ngurra, the SKA-Low construction camp. This has been gifted a Wajarri name meaning ‘Zebra Finch home’. It is one of the many names at the observatory bringing Wajarri language into everyday use on site.

The day-to-day work for the field technicians involves building antennas, installing them in their stations, and getting everything connected into the smart boxes on each station. They’ve also started installing the components of the signal processing system within the remote processing facilities already on site.

“The antennas come in flat packs, so we get them out of a shipping container, get them organised and then in the workshop tent where we put them together and then move them out to the mesh,” Emily says.

“Being in the airconditioned tent is a bit of a luxury in the hot outback environment.”

“It’s a great team. We get along really well and the chemistry is great. We have a good laugh and we trust each other,” Lockie says.

Looking to the future

The field technicians are already the most experienced group on the ground working with the SKA-Low telescope’s systems. Soon they will lend that expertise to future teams hired to continue building the telescope components.

For SKA-Low Telescope Director, Dr Sarah Pearce, that’s a key driver for ensuring the future of her team.

“Australia has always wanted to ensure the SKA project provides opportunities for growth and building new skills. The new field technician roles are designed to give participants the experience they need to end up leading and training future teams building the SKA-Low components on the ground,” Sarah says.

The field technician team's expertise will also be transferable across many industries, including telecommunications and mining.

This is just one part of the benefit the SKA project brings to Australia. The SKA-Low team is creating opportunities within the community across many fields including science, software development, and computing. Whether this group of field technicians continue working on the SKA-Low telescope in the future or move to other projects or industries, this project will have succeeded in growing Australian capability.

Emily looks forward to the opportunities working on the field technician team will bring.

“The great thing about this project is we’re building and assembling a telescope, and then we get to maintain it. There will be many options for me outside of this. I find it very exciting,” Emily says.

Emily Goddard attaches the Low Noise Amplifiers (LNAs) to the top of an SKA-Low antenna. Credit: SKAO.

Once complete, the SKA-Low telescope has a 50-year planned lifetime.

Growing up in WA, Emily has been hearing about the SKA project for more than 15 years.

“My family and I have known about it forever. My sister’s excited, my dad’s excited, everyone in my family is as excited as me,” Emily says.

“I feel incredibly blessed to be given this opportunity, to be given so much teaching and learning.”

The current SKA-Low field technicians are paving the way for the future generations that will be needed to maintain the telescope in top condition.

Lockie is also looking to the future and the role of his community in the SKA project.

No images found.

“I want to learn to teach younger generations how to build these antennas, pass that knowledge down and be a good role model within my community,” Lockie says.

For Lockie, working on the SKA-Low telescope is about more than the interesting technology and everything he’s learning.

“It’s also just being out on the Country around us. I love being able to work out here on Country,” he says.

“My ancestors are from here and being out here is closer than I’ve ever been to my heritage.”

Credits

-

Author

Kirsten Fredericksen and Liz Williams

-

Production editor

-

Editor

Summer Goodwin

-

Developer

Kate Cochrane

-

Visuals and video content producer

Sebastian Neuweiler

-

Images

CSIRO Archive and SKAO